Testing Out Blogdown

Getting a bit of practice with the blogdown workflow

By Gabriel Mateus Bernardo Harrington

June 5, 2020

Hello world!

This is my very first blog post using an R Markdown file within blogdown.

The three prior blog posts on this site came with the template, but I’m leaving them there for now as they are great introductory resources for using Academic.

This post (and this whole site!) wouldn’t be possible without the excellent teaching material from Dr. Alison Hill, and the lovely people who made R and her many brilliant packages for which I offer all the gratitude I can muster!

For practice, I’m going to demonstrate how we can include the following in a single post:

- R code

- A plot

- An image (via markdown syntax)

- An image (via

knitr::include_graphics) - A relative link to another section in my site

- Reading in data

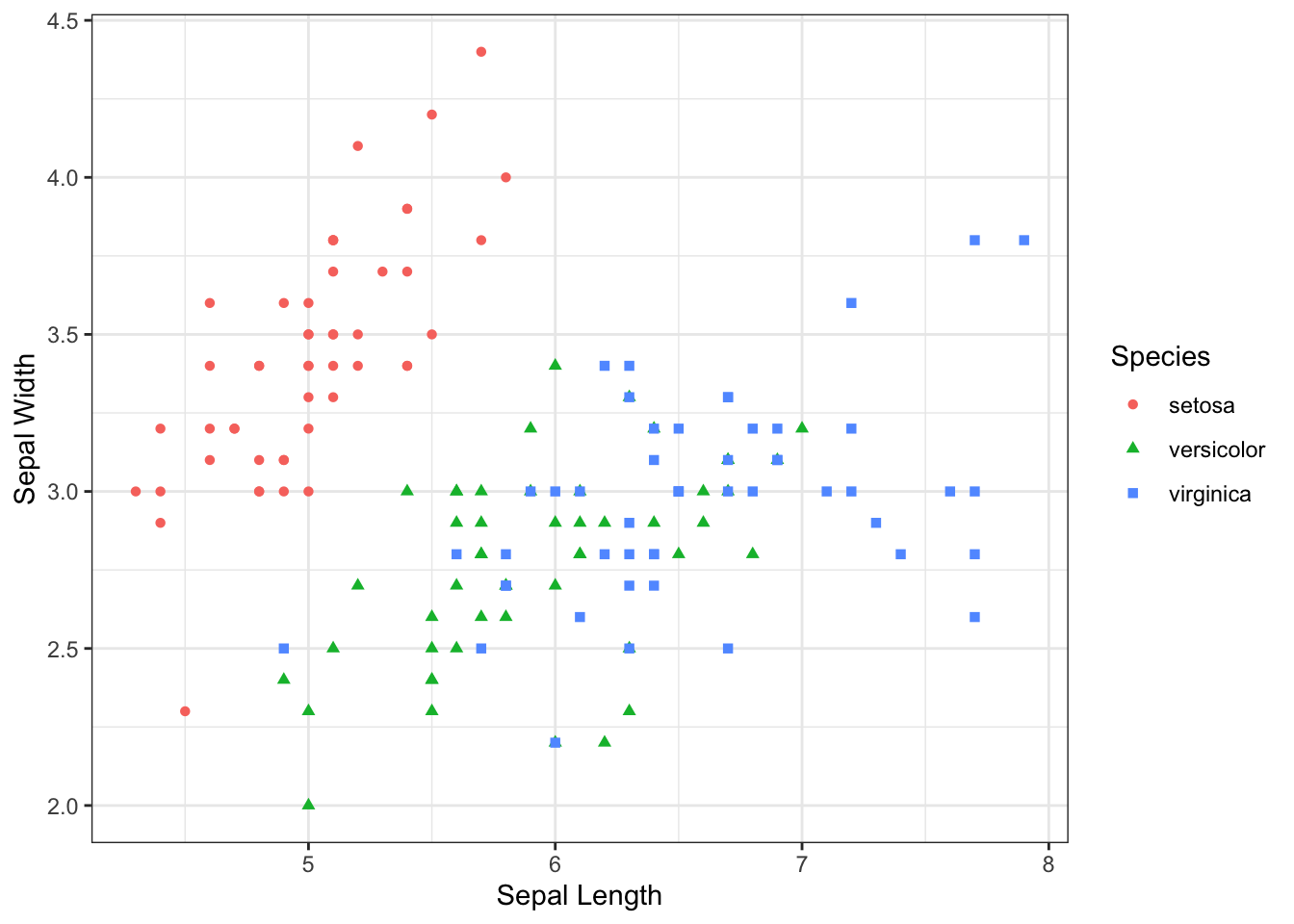

1) Iris data set

Let’s make a plot using the iris data set in ggplot2.

library(ggplot2)

# Dataset

knitr::kable(head(iris))

| Sepal.Length | Sepal.Width | Petal.Length | Petal.Width | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.2 | setosa |

| 4.9 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | setosa |

| 4.7 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | setosa |

| 4.6 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 0.2 | setosa |

| 5.0 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 0.2 | setosa |

| 5.4 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 0.4 | setosa |

2) Plotting

scatter <- ggplot(data=iris, aes(x= Sepal.Length, y = Sepal.Width))

scatter + geom_point(aes(color=Species, shape=Species)) +

xlab("Sepal Length") + ylab("Sepal Width") +

theme_bw()

3) Embedding a bundled image

Using markdown syntax  to generate the image below:

4) Using knitr

We can also accomplish this with a code chunk, setting the following parameter out.width="500px", fig.align='center'

knitr::include_graphics("cute-red-panda-40.jpg")

Figure 1: We can do nice auto-numbered captions as well! Image credit: Unsplash

5) Relative links

I can also include some relative links to, for example, tell you to check out this other section of my site!

The structure of relative links is a bit confusing. When specifying the location of the page you want to get to, the reference point is the directory that your post lives in (and NOT the project root directory).

6) Reading in data

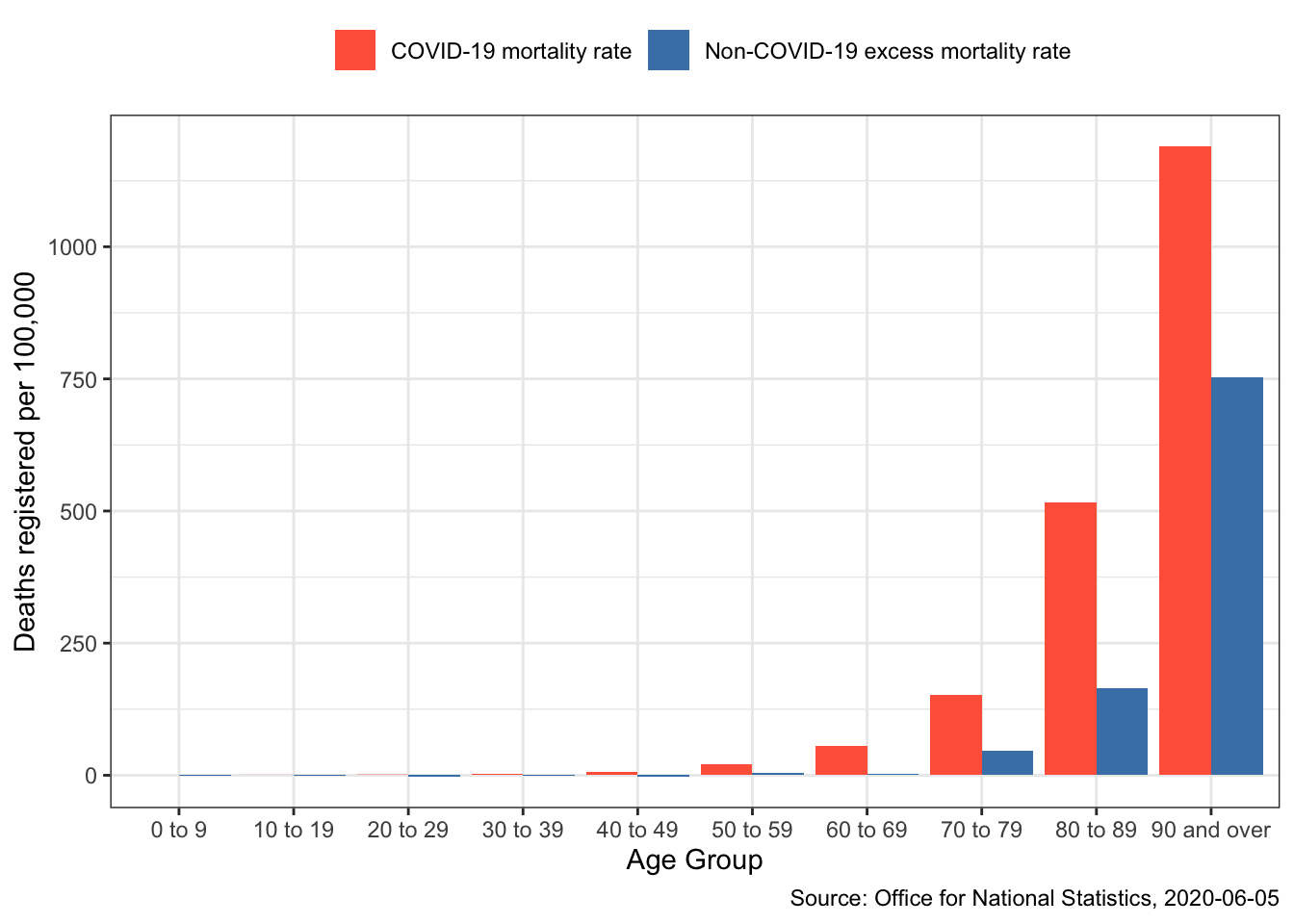

Let’s flex our R muscles a little more by reading in some topical data, and making a fancier plot.

The data is total non-COVID-19 excess deaths per 100,000 and deaths involving COVID-19 per 100,000 for each 10-year age group from England and Wales, Week 11 to Week 18. The numbers around COVID-19 as in constant flux, so please be aware of the date. This data was downloaded from the Office of National Statistics on 2020-06-05.

library(tidyverse)

covid_deaths <- read_csv("covid_deaths_by_age_2020-06-05.csv")

# let's select the rows of actual data

covid_deaths_filtered <- covid_deaths[7:16,]

# set column names

names(covid_deaths_filtered) <- c("age_group",

"non-covid_excess_mortality",

"covid_excess_mortality")

# convert to long-format dataframe

covid_deaths_long <- pivot_longer(covid_deaths_filtered,

-age_group,

names_to = "mortality_type",

values_to = "deaths")

# convert deaths to a numeric

covid_deaths_long$deaths <- as.numeric(covid_deaths_long$deaths)

# plot

ggplot(covid_deaths_long, aes(x = age_group, y = deaths)) +

geom_bar(aes(fill = mortality_type),

stat="identity",

position=position_dodge()) +

ylab("Deaths registered per 100,000") +

xlab("Age Group") +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position = "top",

legend.direction = "horizontal") +

scale_fill_manual(name = "",

labels = c("COVID-19 mortality rate",

"Non-COVID-19 excess mortality rate"),

values = c("tomato", "steelblue")) +

labs(caption = "Source: Office for National Statistics, 2020-06-05")

If you’re curious about explanations surrounding the increase in non-COVID-19 related deaths this article lists some theories.

Interestingly, in the age groups up to 50 the non-COVID-19 death rate has declined slightly

knitr::kable(covid_deaths_filtered)

| age_group | non-covid_excess_mortality | covid_excess_mortality |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 9 | -0.792423313 | 0.014000412 |

| 10 to 19 | -1.056672991 | 0.130274752 |

| 20 to 29 | -2.228613119 | 0.653169144 |

| 30 to 39 | -1.362056932 | 1.944003908 |

| 40 to 49 | -2.631069137 | 6.697752064 |

| 50 to 59 | 4.289242454 | 20.72845098 |

| 60 to 69 | 2.420093746 | 55.40162727 |

| 70 to 79 | 46.66123612 | 152.8772002 |

| 80 to 89 | 165.364023 | 516.5874406 |

| 90 and over | 752.7944396 | 1190.274376 |

And for a little context for these numbers, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents reports that 30-60 people are stuck by lightning each year.

The Office for National Statistics estimated the population in the UK to be 66,796,807 in mid-2019. So if we take then high end of 60 lightning strikes, the odds of getting stuck by lightning in the UK is:

# stop scientific notation

options(scipen = 999)

# calculate risk per 100,000

risk = (60 / 66796807) * 100000

# print result

print(paste(

"The incidence rate of lightning strikes per 100,000 = ",

round(risk, 5),

sep = ""

))

## [1] "The incidence rate of lightning strikes per 100,000 = 0.08982"

So if we assume all humans are equally likely to get stuck by lightning in a given year, then it’s several times more likely for a 0-9 year old to get stuck by lightning than die with COVID-19.

I should stress that this isn’t to make light of COVID-19, many people are dying, and no effort should be spared wherever this can be prevented. If anything, this should highlight how damaging COVID-19 is with a relatively low fatality rate. This pandemic could easily be even worse than it already is with more lethal pathogen behind it, and it is perfectly within the realm of possibility that the next pandemic, which is sadly inevitable, will star a deadlier disease. My greatest hope is that we can use this event as a wakeup call to stop ignoring the scientists who have warned this would happen repeatedly, and prepare better to mitigate future pandemics.