First Publication!

Celebration and summary of my first (first author) academic paper

By Gabriel Mateus Bernardo Harrington in Academia

July 27, 2020

Happy days!

So I finally got my first proper publication! The paper is open access now as well!

Proper here meaning I’m first author which, if you aren’t familiar with the fun(?) nuances of academia, is the only authorship that’s worth much (other than last author, which is also good).

It’s not that middle authorships are worthless.

It’s that they’re almost worthless.

And to think, it only took just over a year (╥﹏╥)

My first actual authorship (which was a second authorship. Confused yet?) was for the paper this publication follows on from and that I briefly touch on in my previous post.

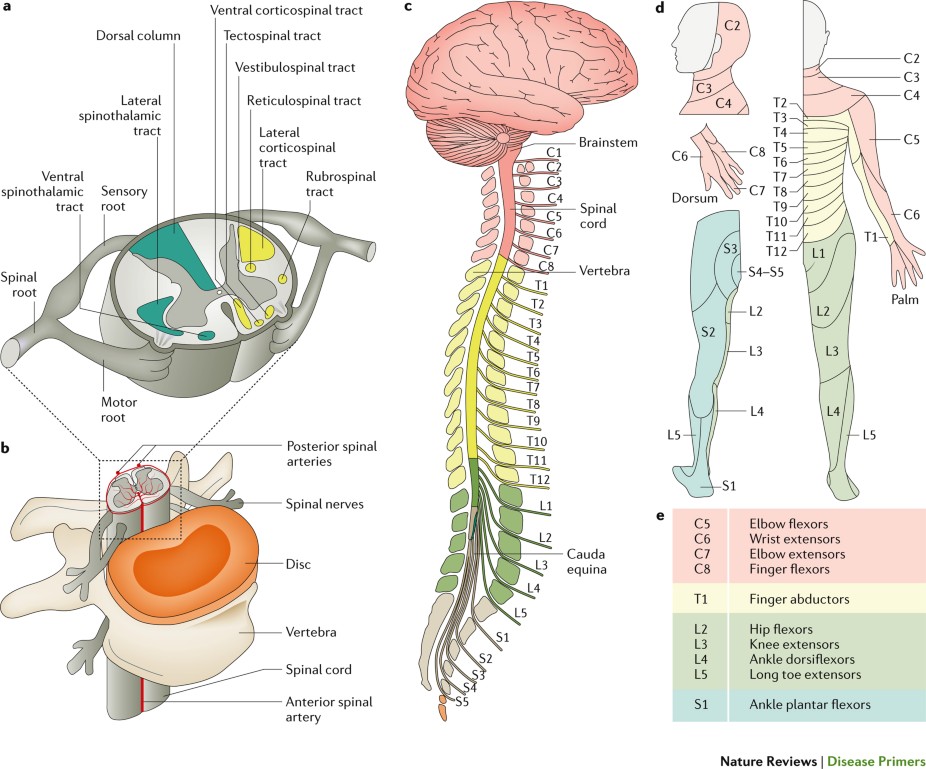

Both of these papers are about prognostic modelling of spinal cord injury. The rest of this post aims to summaries this work in a (hopefully) lay-friendly way, so even a non-academic can get the gist of things.

I do this because my research, like the majority of science, is funded by the taxpayer, and so I feel the taxpayer should have access to the work for free and in a way that they can understand.

Also so I can continue my endless quest to procrastinate on my thesis, but that’s a tad less romantic so let’s not dwell on it.

So what’s prognostic modelling anyway?

Figure 1: Artist rendition of me pretending to work. Except not really. Image credit: iStock

A prognostic model is something that aims to predict outcomes. In our context we’re trying to predict the neurological outcome (their motor and sensor function) for a patient following a spinal cord injury (SCI).

Currently it’s very difficult to know what sort of state a SCI patient will be in one year after injury for example. This is a problem for two main reasons.

Firstly, it’s rather unpleasant for patients to be left with little idea as to what’s going to happen to them. They may ask questions like:

- “Will I be able to walk again?”

- “Will I be able to feed myself?”

- “What about bathing, dressing and grooming?”

To which a clinician is often unable to give any answer beyond “No” in the most severe SCI cases and “I don’t know” in other cases, which is the majority of the time.

Figure 2: What does it even mean to “know” something in these crazy times anyway…? Image credit: Giphy

This uncertainty can end up making some patients unrealistically hopeful about their prospects, and others overly pessimistic, both of which can have a negative impact on mental health in both the long and short term.

Secondly, as the level of spontaneous recovery varies wildly across patients, developing new therapies to treat SCI is extremely difficult. Imagine you have some fancy new therapy which you give to say 10 SCI patients. Half of them improve dramatically and nothing noteworthy happens to the other half.

Was it your therapy that induced the improvement, or would those patients have recovered regardless of what you did or didn’t give them?

Due to this, studies need very large sample sizes to account for the possibility of spontaneous recovery and prove a therapy is effective. This massively increases the costs of testing therapies which slows their progress.

Therefore, this research aims to see if we can predict patient outcomes on admission to hospital.

Okay, so how did your papers go about attempting this?

Right, so without wishing to go into somewhat complex math, we took a bunch of data relevant to the patient injury, such as initial injury severity, age, diabetes status, etc., and built several models which aim to predict outcome scores for motor and sensor function at discharge and 12-months post-injury.

Importantly, we also included any blood tests that were taken as part of routine care. To be clear, these are not blood tests that we scientists requested be done, but just done as part of normal care. We’re interested in routine bloods because we suspected they could provide valuable insight into outcomes at no additional cost to the healthcare provider, as the data had already been collected anyway.

This is in contrast to most of the other literature in this field, which focuses on cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). CSF would almost certainly have useful information for predicting SCI outcomes, but a very invasive procure is required to collect it, which introduces additional cost for the healthcare provider and risk to the patent.

Figure 3: A nice cartoon of the spinal cord that illustrates which parts of the cord control which myotome (muscle groups). Image credit: Nature Reviews

And the results?

In brief, it worked.

I should stress at this point, for all my preamble, the main focus of the work at this stage is more to see if routine bloods can add predictive value for SCI outcomes rather than actual build a model that could be used in clinic.

The models we built were reasonably accurate at predicting outcomes, but to create something good enough to use in the clinic we would need an enormous sample size that goes way beyond the scope of these two papers. To give you a sense of scale, we used around 80 patients in our first preliminary paper and around 430 in this follow-up paper. We’d need many thousands if we wanted to propose the model be used in clinic.

We do hope to get there someday, but that’s certainly beyond the scope of my PhD so meh ¯\( ͡ಠ ͜ʖ ͡ಠ)/¯

However, these papers provided evidence that routine blood markers can be somewhat predictive out outcome, which is what we were interested in.

So happy days!

Figure 4: One happy looking rabbit. I wonder what drugs they gave it… Image credit: Giphy

Both papers also suggest that several blood markers associated with liver function add value to predictions of outcome. This has peaked our interest and we hope to further investigate this link in subsequent work.

My next work will involve looking at SCI patient plasma with proteomics to see what differences there are in protein expression between people who experience significant neurological recovery as compared to those who don’t. Here’s hoping it doesn’t take another year to publish!

Feedback welcome!

So I’m of the opinion that most academics are crap writters. This is often attributed to academics writing in a way that’s overly complex to sound smart.

I think this is part of it, but personally I have been explicitly told to make my writing my complex, usually to cater to journals. The reality is that journals can often shun better written, more understandable prose and demand they be made “fancier”.

This is just another reason why academic journals are the worst. Fair warning, don’t read that article if you’re having a good day, it’ll ruin it.

As a result of this I really don’t have much of a gauge of how good I am at writing for a lay audience. So I welcome any feedback you might have about my writing as I’m keen to improve!

Thanks for reading, and have one final celebratory .gif for the road

Figure 5: \( ͡> ‿‿ ͡<)/ Image credit: Giphy